Part 1 of The Economics of Data Architectures in 2026

The Modern Data Stack is Dead

The Modern Data Stack (MDS) was never an architecture. It was a philosophy: best-of-breed tools, loosely coupled via APIs, separation of concerns. Fivetran for ingestion. Snowflake for storage. dbt for transformation. Looker for visualization. Buy the pieces, assemble yourself.

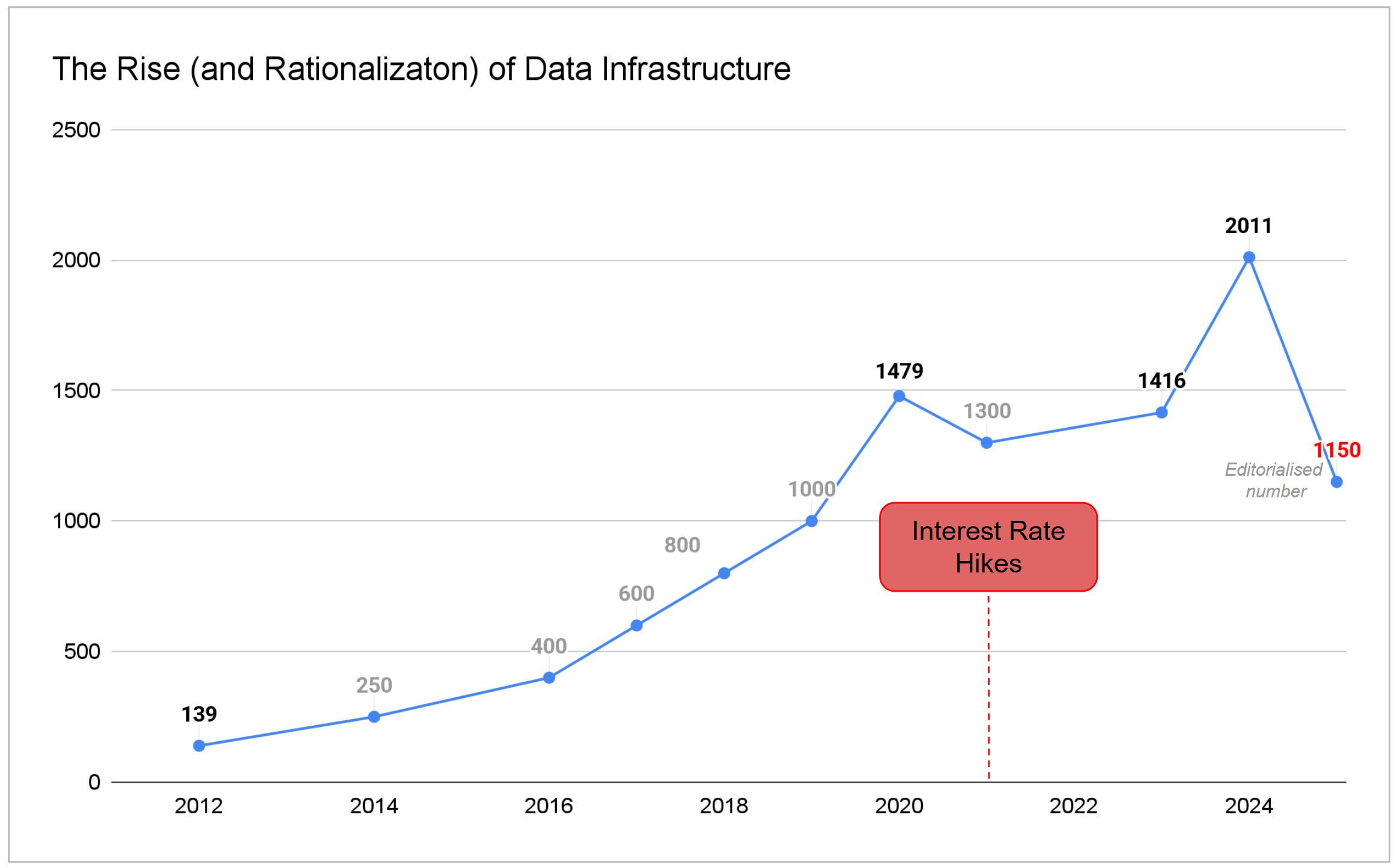

It worked when capital was cheap. Between 2020 and 2021, venture capital poured $5.24 billion into data infrastructure. The MAD Landscape exploded to 1,416 companies. Every function got its own startup.

Then interest rates rose starting in 2022, and suddenly integration costs mattered.

Figure 1: Companies of Matt Turck’s MAD landscape, 2012 to 2025. From 139 logos to 2011 at peak, then a deliverable editorial cut. Approx values are estimated from report context where exact counts were not published.

Today, 70% of data teams juggle 5-7 different tools just to manage daily workflows. 40% cite maintaining integrations as their highest cost center. The “best of breed” philosophy created a tax that most organizations can no longer afford.

The response has been market consolidation. Fivetran and dbt merged in late 2025, combining into a $600M ARR entity. IBM acquired Confluent for $11.1 billion. Starting in 2023, Microsoft bundled everything into Fabric (An interesting expose into what next gen platform architecture could be). Databricks and Snowflake keep expanding scope.

The MDS era is over. What replaces it isn’t a single architecture but several competing patterns, each with different economic tradeoffs. Understanding those tradeoffs matters more than understanding the technology.

Seven data architectures and their economics

Every architectural pattern is really an economic thesis in disguise. Here’s what each one is betting on.

Data Warehouse (Cloud-Native)

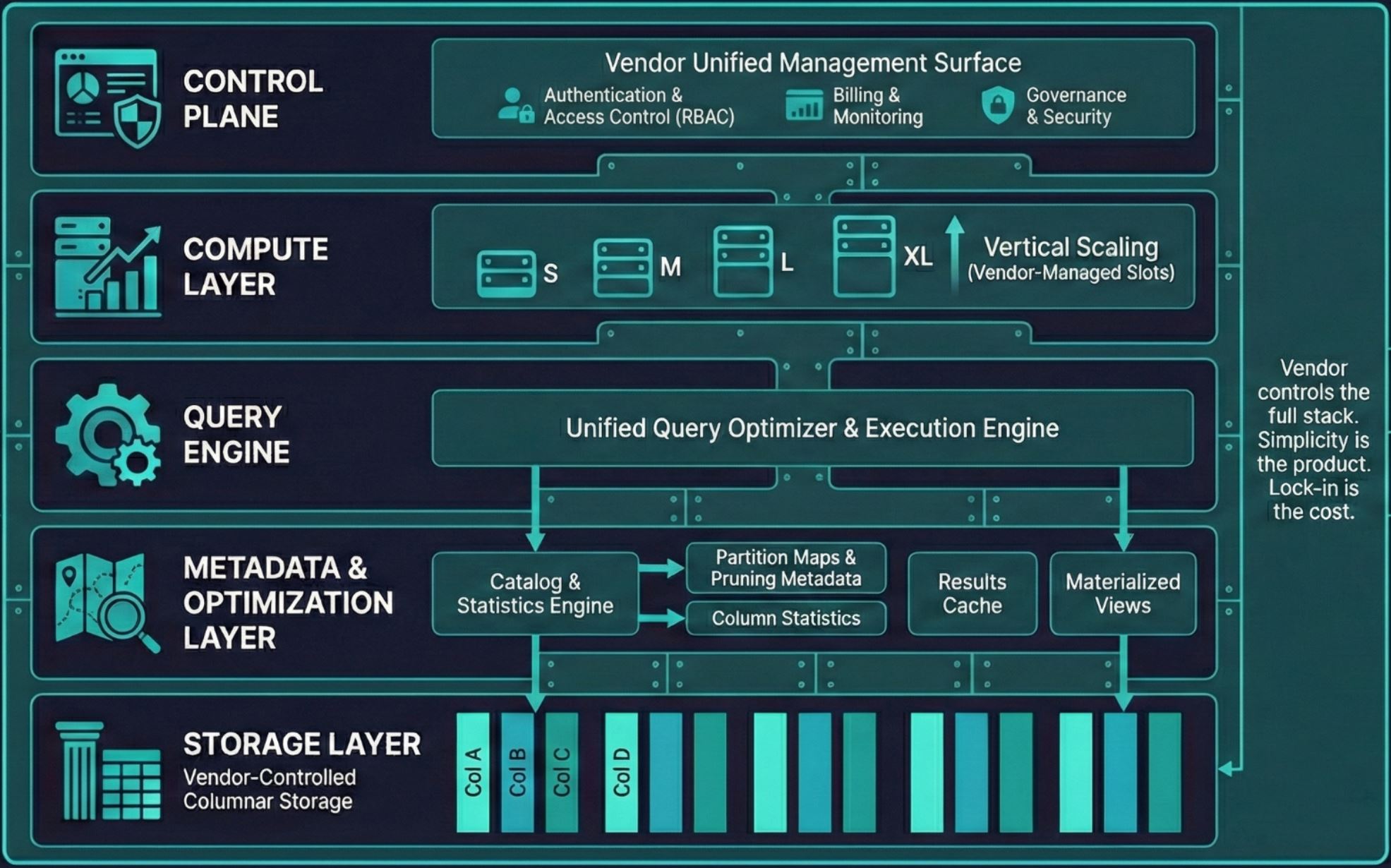

The warehouse is the oldest pattern, now reborn in the cloud as a scale out managed service. Snowflake, BigQuery, Redshift, Azure Synapse. A single system where storage and compute are bundled together. You load data in, you query it out.

The economics: Centralization reduces coordination cost. One system, one team, one bill. The vendor handles infrastructure so you don’t need an army of DBAs or platform admins.

The tradeoff: The vendor controls the economics. Snowflake’s pricing is simple, but 90% of your bill is query compute, and they set the rates. Switching means replatforming everything.

Adoption: Around 79% of organizations use a data warehouse. It’s the default.

Data Lakehouse

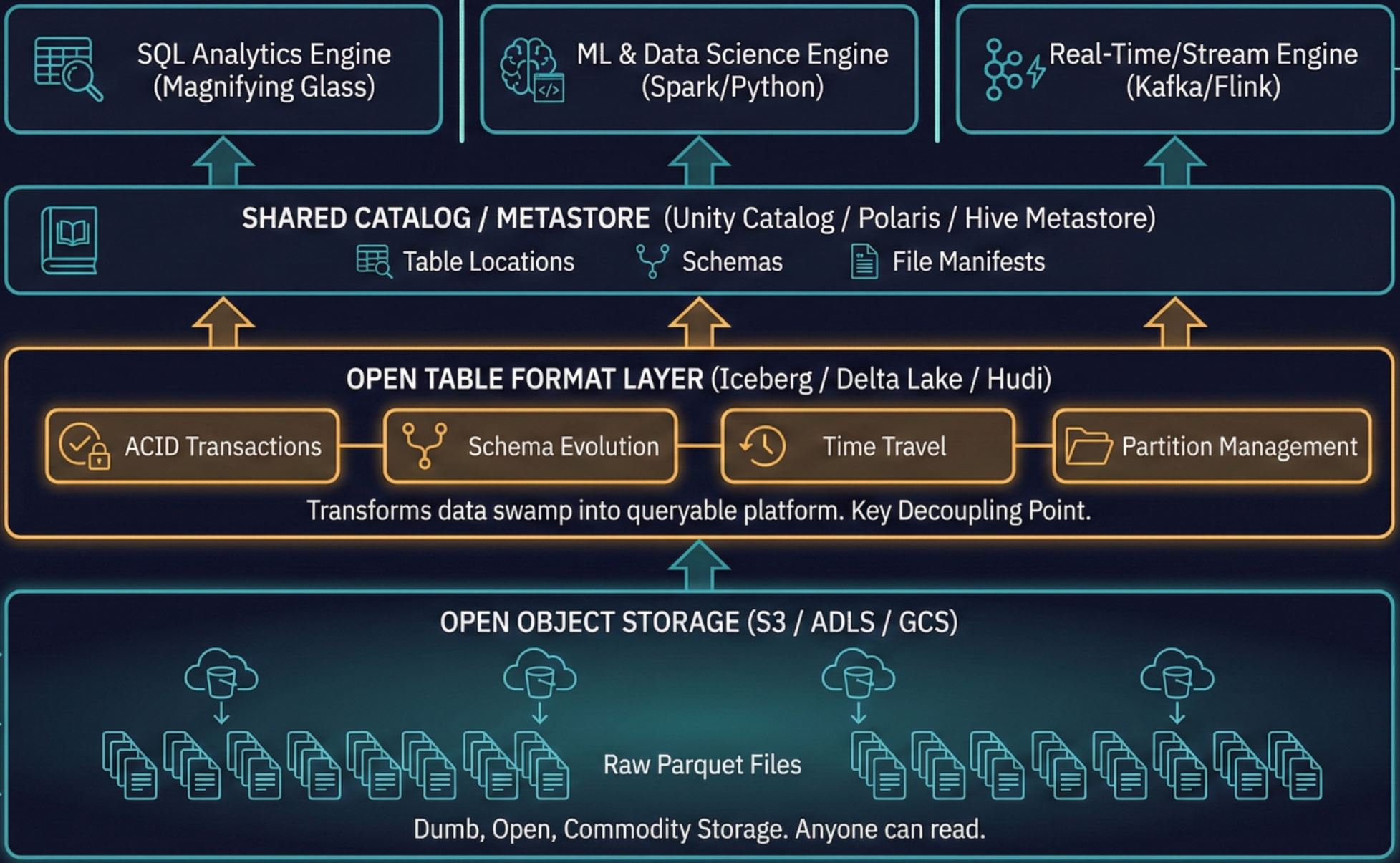

The lakehouse emerged in early 2020, primarily from Databricks, as a response to a specific inefficiency: organizations were paying twice. Once to store data in a cheap lake (S3, ADLS). Again to copy it into an expensive warehouse for querying. The ETL between them was a tax on every insight.

The economics: Store data once in open formats (Iceberg, Delta Lake, Hudi). Bring any compute engine to it. Eliminate the duplication. Commoditize storage, compete on compute.

The tradeoff: More operational complexity. Databricks’ “two-bill problem” means you pay them for software and your cloud provider for infrastructure separately. You can optimize aggressively (spot instances can cut compute costs up to 90%), but you need engineering capacity to do it.

Adoption: Somewhere between 8% and 65% depending on how its measured. A 2023 BARC survey found 8-12% with distinct lakehouse implementations. A Dremio survey found 65% of participants running the majority of analytics on lakehouse platforms. The gap reflects definition differences. Either way, adoption is accelerating.

Data Mesh

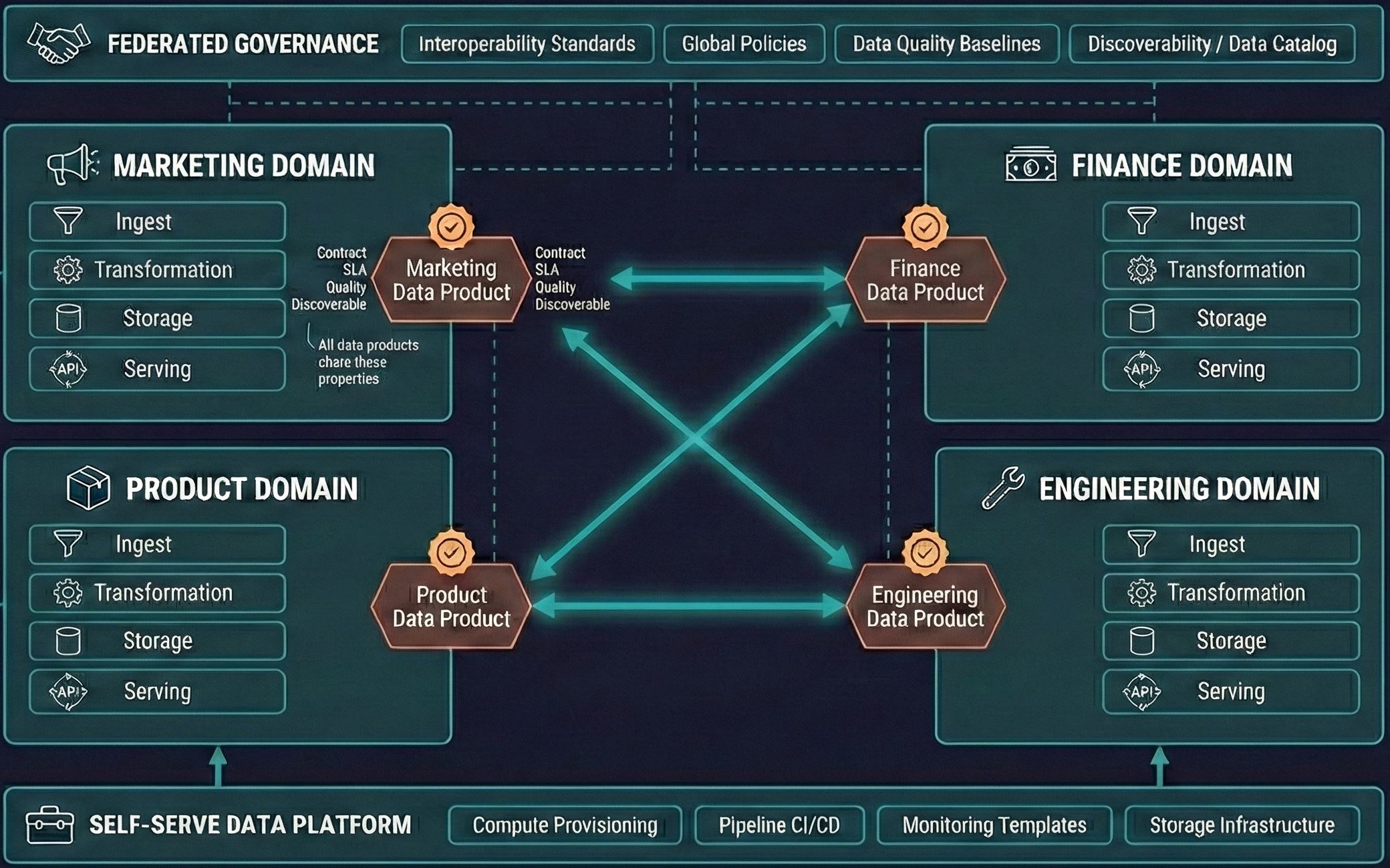

Zhamak Dehghani coined “data mesh” in 2019 while at ThoughtWorks. It’s not a technology choice. It’s an organizational design. Where fabric virtualizes access from the top down through metadata and automation, mesh federates ownership from the bottom up through domain teams. Instead of a central data team owning everything, domain teams (Marketing, Finance, Product) own their own data as products. A thin platform layer provides self-serve infrastructure. Federated governance keeps things consistent.

The economics: Central data teams become bottlenecks at scale. The marginal cost of adding a new data product keeps rising because everything flows through the same people. Mesh flattens that curve by distributing ownership to the people with the most context.

The tradeoff: Higher total headcount. Each domain needs data talent embedded. Implementation takes 12-24 months for full enterprise rollout. Gartner’s 2024 Hype Cycle placed mesh in the “Trough of Disillusionment” and questioned whether it would ever reach mainstream adoption.

Adoption: Adoption remains niche. Gartner’s 2024 Hype Cycle placed mesh in the Trough of Disillusionment. Only 18% of organizations had the governance maturity to attempt it as of 2021, and combined mesh/fabric influence reached just 18% of data programs by 2024. The pattern makes sense for companies with genuinely distinct domains. For everyone else, the coordination overhead may exceed the bottleneck it solves.

Data Fabric

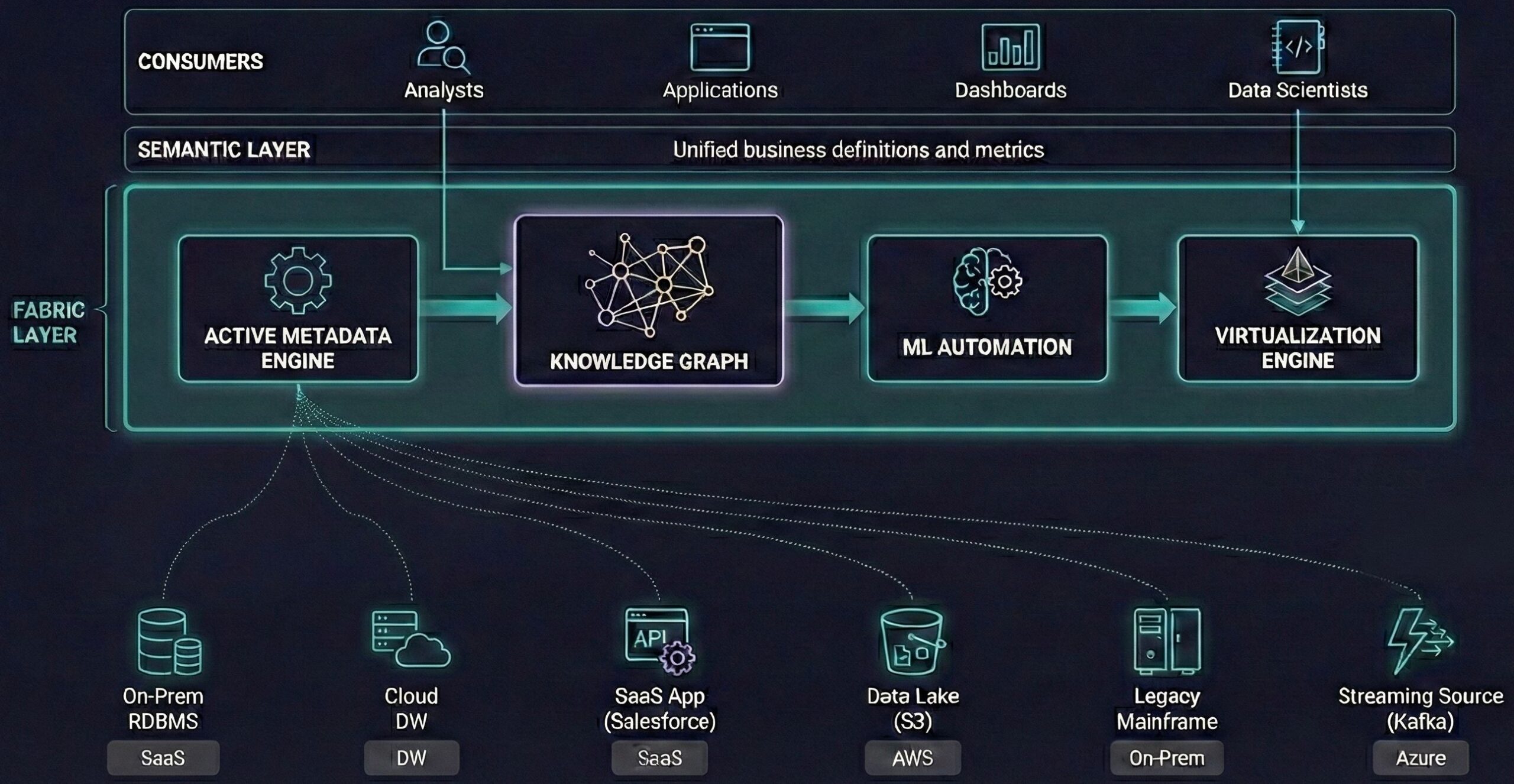

Data fabric is Gartner’s answer to mesh. Instead of reorganizing people, automate the problem away. A fabric uses active metadata, knowledge graphs, and ML to discover data across disparate sources and automate integration. The data stays where it is. The fabric virtualizes access.

The economics: Labor is the most expensive part of the data stack. Schema mapping, pipeline building, lineage tracking. All high-cost, low-value work. Automate it.

The tradeoff: Query performance. Virtualizing across sources means federated queries, which are slower than local ones. You also need the governance (metadata layer) to actually work, which requires maturity most organizations don’t have yet.

Adoption: Around 10%, with many POCs underway. Gartner claims properly implemented fabrics can reduce data management effort by 50%. The market is projected to grow from $3.25B (2024) to $19B (2033). Vendors like Denodo and the cloud-native catalog tools are chasing this.

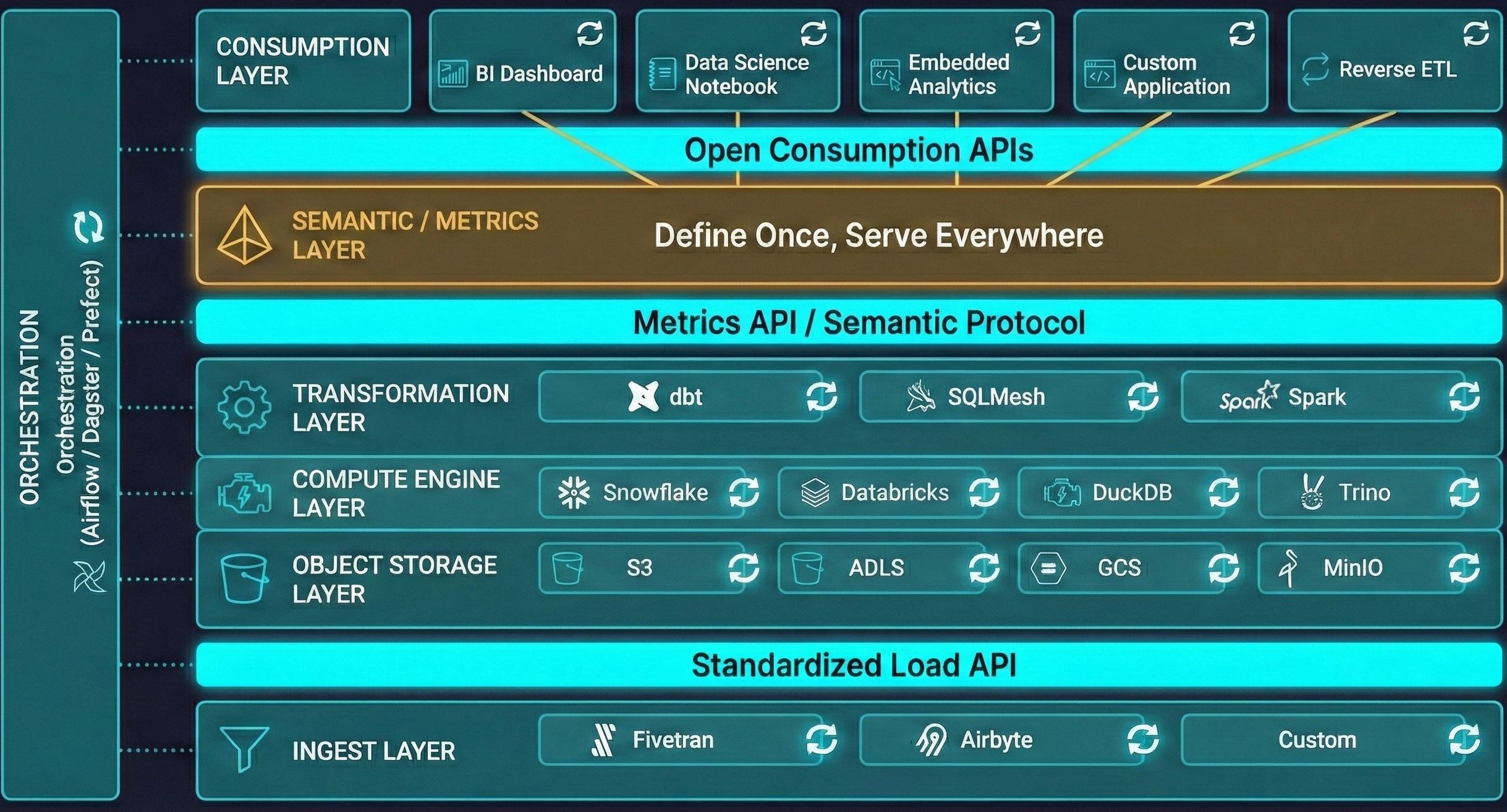

Composable / Headless

The composable stack is the MDS philosophy refined. Instead of just “best of breed,” it emphasizes open standards and swappable components. Metrics defined once in a semantic layer, served to any tool. Open table formats so you’re not locked to one warehouse. APIs everywhere.

The economics: Avoid lock-in. Keep optionality. Reduce the “data copy tax” where every downstream tool needs its own replica.

The tradeoff: The integration tax is still real. The 40% who cite integration as their highest cost are often running composable stacks. The theory is cleaner than the practice.

Adoption: Hard to measure because it’s more mindset than product. The growth of open table formats (Iceberg adoption, Parquet standardization) suggests the principles are spreading even if the label isn’t.

Streaming-First

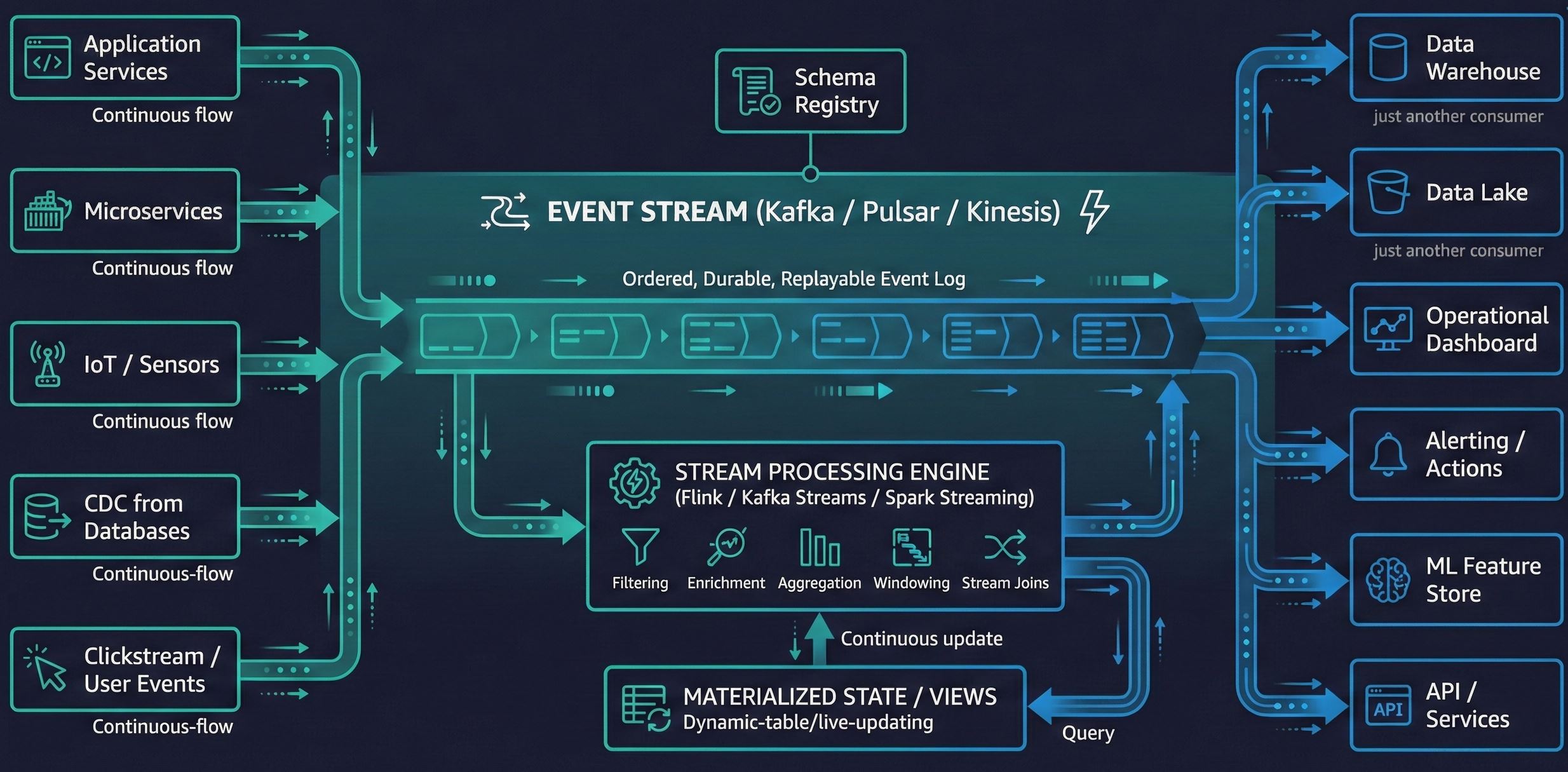

In a streaming-first architecture, events are the backbone. Instead of batch ETL that runs overnight, data flows continuously through a stream (Kafka, typically). Processing happens in real-time. The lake or warehouse becomes a consumer of the stream, not the source of truth.

The economics: Data has time value. Batch processing creates latency between when something happens and when you can respond. For operational use cases, and especially for AI agents that need current context, that latency is unacceptable.

The tradeoff: Operational complexity. Streaming systems are harder to debug, harder to reason about, and require different skills than batch. Not every workload needs real-time.

Adoption: 72% of organizations now use data streaming for mission-critical systems, according to Confluent’s 2023 survey of 2,250 IT leaders. Kafka runs at over 80% of the Fortune 100. The infrastructure is mainstream. The question is how central it is to your architecture versus a bolt-on for specific use cases.

LLM-Ready

I purposefully did not use the term “AI” here because I wanted to get to the source of the thing, not the marketing nomenclature.

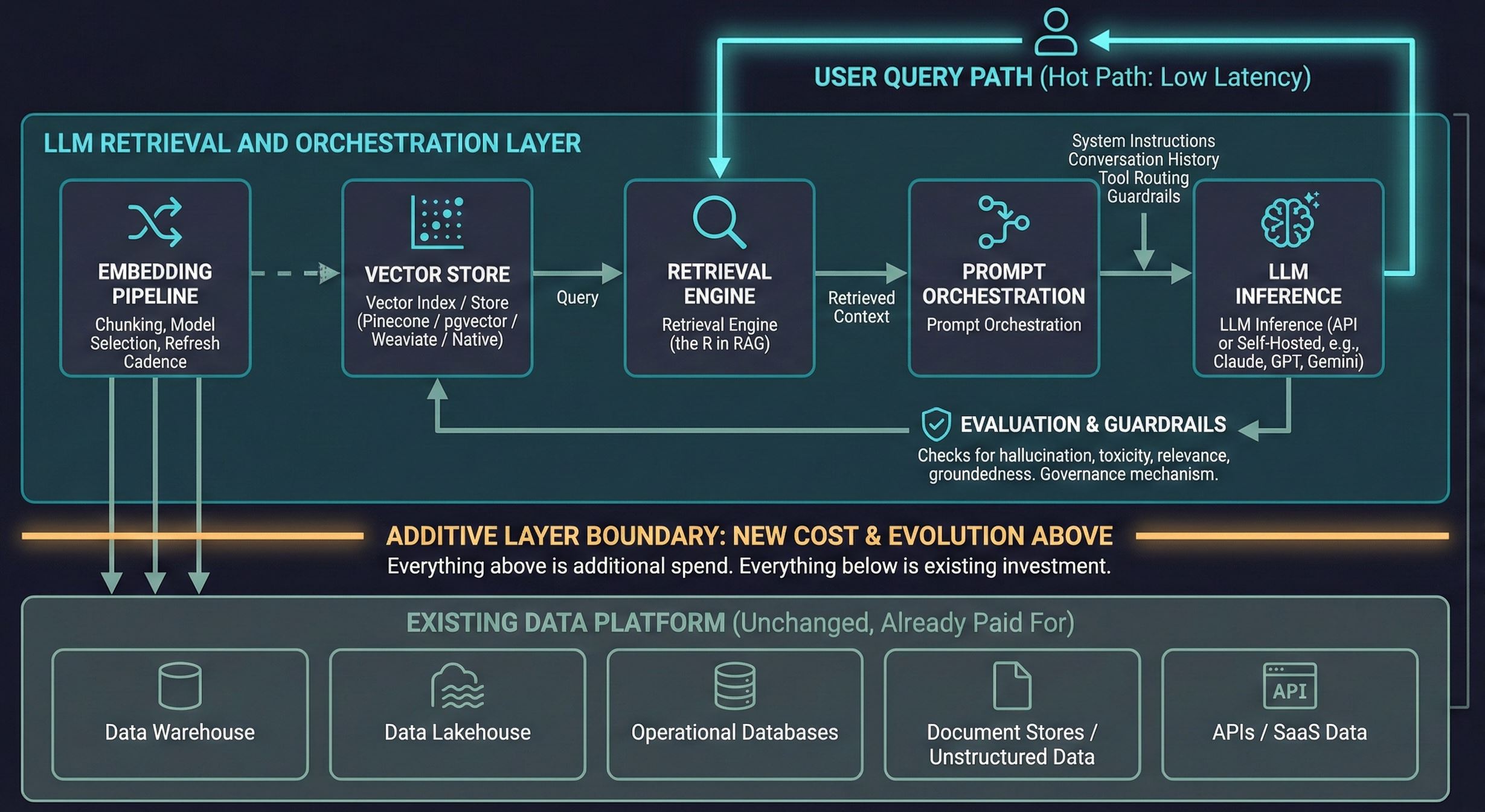

The newest pattern, and the least settled. LLM-ready architectures add a retrieval and orchestration layer on top of existing data platforms to serve large language models at inference time. The core problem: an LLM needs the right context, from the right sources, in the right format, fast enough to be useful. That means embedding pipelines, vector indexes, prompt orchestration, and evaluation frameworks layered over whatever warehouse or lakehouse you already run.

This is not a replacement architecture. It is an additional cost layer. Your warehouse still serves BI. Your lakehouse still runs batch analytics. The LLM stack sits alongside them, consuming their data through retrieval pipelines. The infrastructure question is not “rebuild for LLMs” but “what do I add, and what does that addition cost?”

The economics: LLMs are becoming the primary interface between people and enterprise data. Enterprise generative AI spending tripled from $11.5B to $37B in a single year (Menlo Ventures, 2025). The organizations that can feed their models accurate, current context will outperform those that cannot. The retrieval layer is where that advantage is built.

The tradeoff: Maturity and cost transparency. RAG dominates at 51% adoption among enterprises deploying LLMs, up from 31% the prior year. But the patterns are still evolving rapidly. Prompt engineering remains the most common customization technique. Fine-tuning is rare. Only 16% of enterprise deployments qualify as true agents . Most production systems are simpler than the marketing suggests. Best practices for chunking, retrieval, evaluation, and orchestration shift quarterly. You are building on ground that has not finished moving.

Adoption: Early but accelerating. The infrastructure layer (storage, retrieval, orchestration connecting LLMs to enterprise systems) reached $1.5B in spend in 2025, while model API spending doubled to $8.4B. Every major platform is adding retrieval capabilities natively: Snowflake Cortex, Databricks’ Vector Search, Postgres with pgvector. The dedicated vector database market (Pinecone, Weaviate, Milvus) is growing, but the bigger story is existing platforms absorbing the functionality. The “LLM-ready” layer is being folded into incumbent ecosystems, not replacing them.

Architectural Convergence

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: these aren’t seven independent choices.

The market is converging. Databricks and Snowflake both adopted open table formats. Both added streaming capabilities. Both are building AI features. Microsoft Fabric bundles warehouse, lake, streaming, and BI into one offering. IBM buying Confluent signals streaming folding into enterprise platforms.

The “architecture” question is increasingly becoming “which ecosystem.” The patterns matter less than understanding that we’re heading toward 3-4 major platform ecosystems, with open formats providing a (limited) escape valve for portability.

What differs is the economic model underneath: who bears the coordination cost, where lock-in lives, what skills you need, and who captures value.

Decision Matrix

| Architecture | Economic Thesis | Key Tradeoff | Choose If… |

| Warehouse | Centralization reduces coordination | Vendor controls economics | BI-first, want simplicity, can absorb vendor pricing |

| Lakehouse | Eliminate ETL tax, commoditize storage | Operational complexity | ML workloads, engineering capacity to optimize |

| Mesh | Distribute ownership, flatten cost curve | Higher headcount, long implementation | Large org, distinct domains, 12+ month runway |

| Fabric | Automate integration labor | Query performance, metadata maturity | Data sprawl problem, strong metadata foundation |

| Composable | Avoid lock-in, maintain optionality | Integration tax still real | Multi-cloud mandate, strategic fear of lock-in |

| Streaming | Time value of data | Operational complexity | Operational use cases, real-time requirements |

| LLM-Ready | Optimize for what’s next | Immature, shifting ground | GenAI central to product, greenfield build |