The Economics of Data Gravity

In 2010, Dave McCrory introduced the concept of “data gravity” to describe a phenomenon IT professionals were increasingly experiencing: as data accumulates in one location, it becomes harder to move, and the systems that depend on it tend to cluster nearby. The metaphor suggested that data, like physical mass, exerts a gravitational pull – applications would move closer to large datasets to minimize latency and bandwidth costs.

Fifteen years later, the concept is everywhere. Cloud providers justify egress fees as necessary to recover infrastructure costs. Regulators cite data sovereignty concerns when imposing localization requirements. Infrastructure planners use Digital Realty’s Data Gravity Index to forecast billion-dollar buildouts.

The effects are real and felt daily. DBAs watch backup windows stretch from hours to days. Doctors wait for medical imaging systems to load scans that previously loaded in a shorter time when they have less data stored. CFOs see cloud bills spike not from storage or compute, but from simply accessing their own data across regions. CEOs evaluate multi-cloud strategies and discover that moving workloads isn’t a technical problem but an economic penalty.

I wanted to understand: when we experience these constraints, how much is organic (real technical limitations) versus manufactured (deliberate business model choices)? Because the prescription is radically different depending on the answer.

If data gravity is mostly physics, we optimize infrastructure and architect around it. If it’s mostly artificial, we have a competition and policy problem disguised as a technical one.

How We’re Measuring It Wrong

The conventional approach treats data gravity as a volume problem. Digital Realty’s Data Gravity Index ranks cities by GDP, data center capacity, and aggregate storage. Cloud providers price egress per gigabyte. Regulators track petabytes crossing borders.

But data gravity isn’t one-dimensional. It’s not just about gigabytes on disk or in data files.

Think about what actually makes data hard to move. It’s not just volume. It’s a combination of factors:

- Volume: How much data there is (the mass)

- Dependency/Integration Depth: How many systems and processes rely on it

- Criticality: What breaks if it’s unavailable or moves

- Velocity: How frequently it’s accessed

- Latency sensitivity: How fast it needs to respond

Some examples showing how nuanced and complex this is:

- A 500TB cold archive has massive volume but low dependency, low criticality, low velocity, and low latency requirements. Moving it is time-consuming but not organizationally disruptive. You can plan it, execute it over weeks, and nothing is likely to break.

- A 50TB hospital EHR system has moderate volume but extreme dependency (20 integrated applications), extreme criticality (patient safety), high velocity (50,000 transactions daily, 500 concurrent users), and high latency sensitivity (sub-second response requirements). Moving it isn’t a data transfer problem, it’s an organizational coordination problem with regulatory and safety implications.

Current metrics heavily weight volume while largely ignoring dependency, criticality, velocity, and latency sensitivity. They measure where data accumulates, not what depends on it or what breaks if it moves.

What this means in practice: A 10TB financial trading database with sub-10ms latency requirements and 100+ dependent trading algorithms has far more gravity than a 200TB email archive queried 50 times per month. The archive has 20x more volume. The trading system has 100x more gravity.

The DGx analysis demonstrates the measurement gap. It tracks metro GDP and data center capacity – essentially measuring where volume accumulates. Does it correlate with economic size? Yes. Does it measure gravitational force? No. It tells you where data is stored, not what depends on it, how critical it is, or what breaks if it moves.

A real gravity metric would need to be multidimensional:

- Volume metrics: Storage capacity, aggregate bytes

- Dependency metrics: API call rates, integration points, concurrent users

- Criticality metrics: Business process dependency, regulatory requirements, uptime SLAs

- Velocity metrics: Transaction throughput, query frequency, active vs. dormant data ratios

- Latency metrics: Response time requirements, geographic distribution of access

Without measuring across all these dimensions, we’re collapsing a multidimensional force into a single number. That’s not measurement – it’s lossy compression. And what we lose is precisely what matters: the ability to distinguish between data that’s genuinely stuck and data that’s just big.

But understanding the measurement problem refines the original question. I started asking: how much of data gravity is organic versus manufactured? Now I can be more precise: which dimensions of data gravity are organic constraints we have to architect around, and which are manufactured barriers we could design away?

Because it turns out, not all sources of gravity affect all dimensions equally.

Five Sources of Data Gravity

Different forces create data gravity, and they don’t affect all dimensions equally. Some create genuine technical constraints. Some artificially amplify specific dimensions through pricing or policy. Some are feedback loops from measuring the wrong thing.

Note: sources and dimensions are different things.

- Dimensions describe what data gravity is – the five characteristics (volume, dependency, criticality, velocity, latency sensitivity) that make data hard to move.

- Sources describe where that gravity comes from – the forces that create or amplify those dimensional constraints.

This matters because different sources affect different dimensions. Understanding which source affects which dimension is how we separate organic constraints from manufactured barriers.

Technical Gravity

This is the real physics of data: latency, bandwidth limits, processing locality. Technical gravity primarily affects the volume and latency dimensions – it’s genuinely expensive to move massive datasets, and some workloads genuinely require sub-millisecond proximity to data.

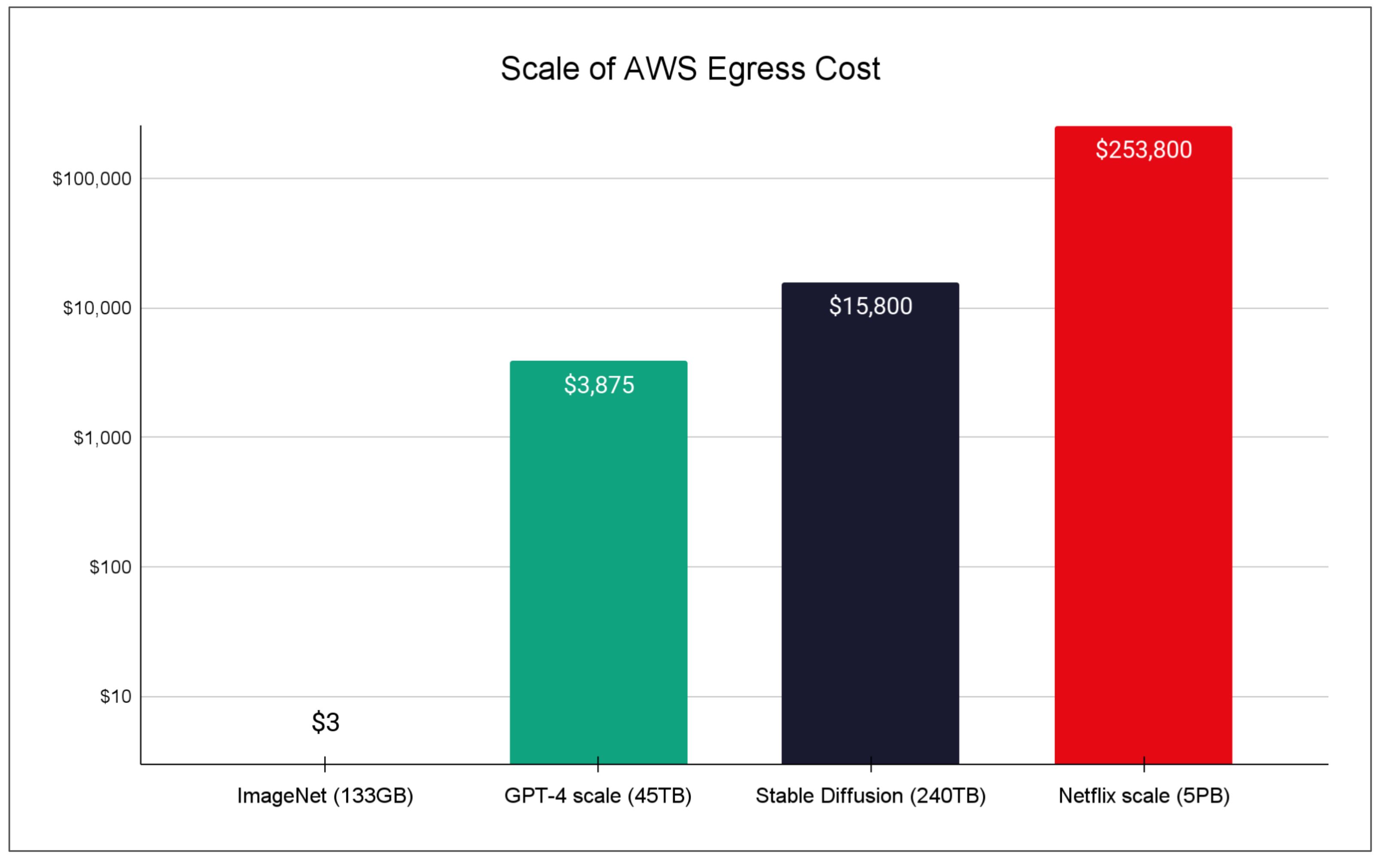

When you’re training a large language model, moving compute to the data often makes more sense than moving data to compute. Consider the costs: a GPT-3 scale dataset used approximately 45TB of training data. At AWS’s standard egress rates ($0.09/GB for first 10TB, dropping to $0.05/GB above 150TB), moving that dataset once would cost roughly $3,875. The LAION-5B dataset used for Stable Diffusion training is estimated at 240TB – roughly $15,800 to move. At petabyte scale, the costs become prohibitive.

Figure 1: Egress cost to move AI training datasets

Technical gravity is real. Moving petabytes has genuine bandwidth and time costs. Coordinating migrations across thousands of distributed databases creates real orchestration challenges. Systems with sub-10ms latency requirements genuinely need proximity to data.

Where technical gravity becomes artificial is when cloud providers amplify it through pricing that exceeds actual costs by 10-80x.

Economic Gravity

This is the socio-economic source: Economic gravity doesn’t create real constraints across all five dimensions. It specifically amplifies the volume dimension through artificial pricing barriers. Here is an example:

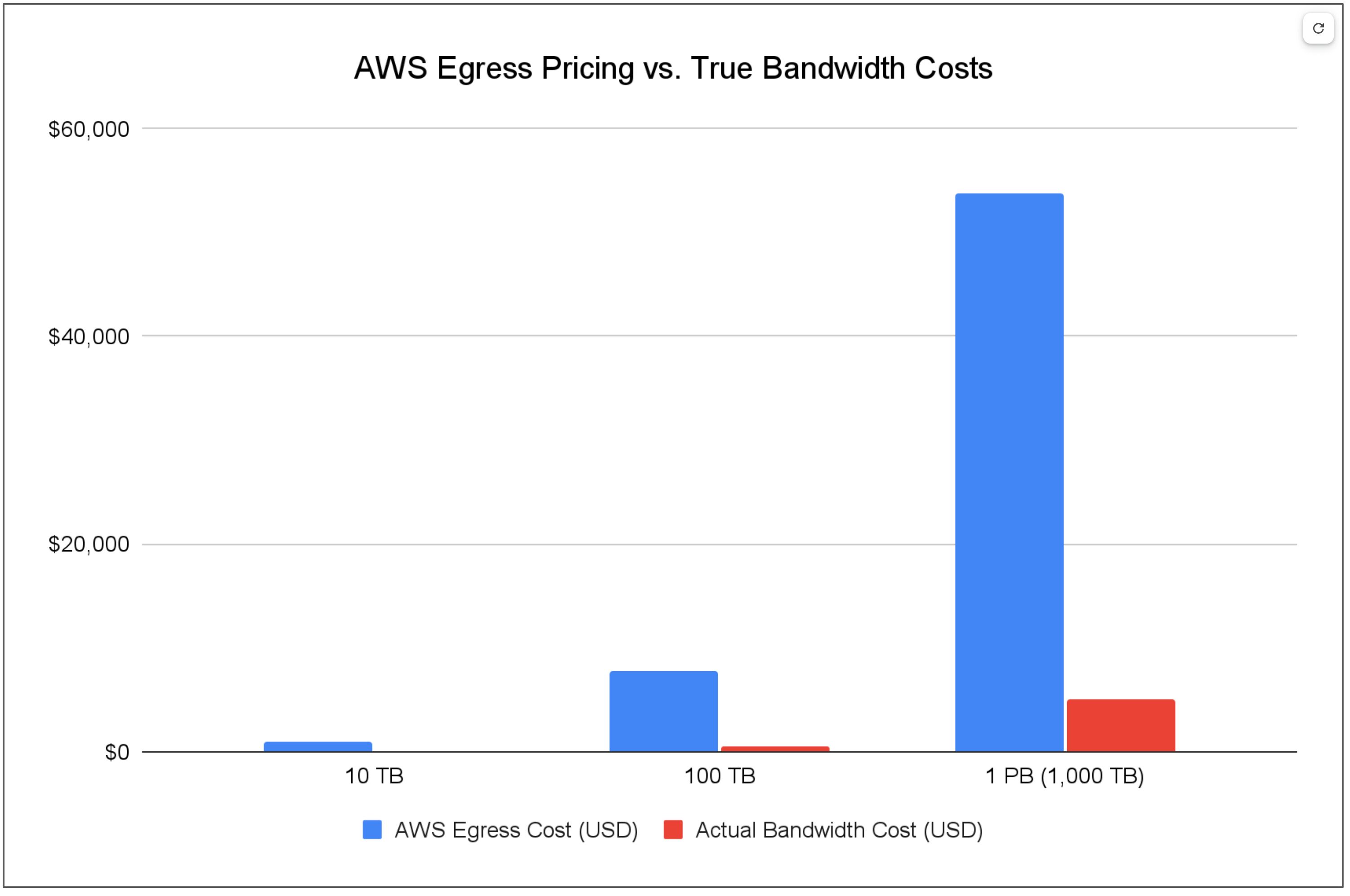

AWS charges $90 to move 1TB of data out. The actual bandwidth cost, based on wholesale transit rates and competitive provider pricing? Approximately $5. That’s an 18x markup.

At 100TB, AWS charges $7,800. Actual cost: $500. Still a 15.6x markup.

At 1PB, AWS charges $53,800. Actual cost: roughly $5,000. Even at a massive scale, that’s a 10.7x markup.

Figure 2: Egress cost compared to bandwidth costs in AWS

How do we know the actual costs? Because alternative providers prove it. Cloudflare documented that AWS’s egress fees represent roughly an 8,000% markup over wholesale transit costs in North American markets. Zero-egress providers like Wasabi and Cloudflare R2 charge nothing for data egress, proving this isn’t about cost recovery. Akamai charges $0.005/GB (roughly $5 per TB), about 18x cheaper than AWS’s initial tier.

Azure and Google Cloud follow similar pricing structures. Azure charges $87 per TB initially (17.4x markup over actual costs). Google Cloud starts at $85 per TB. All three hyperscalers offer volume discounts, but even at the highest tiers, they’re charging 10-15x more than competitive alternatives and 50-80x more than wholesale bandwidth costs.

While economic gravity primarily targets the volume dimension through pricing, it creates cascading effects. Organizations reshape their entire architectures around egress fees – batching operations to minimize transfers (affecting Velocity), centralizing processing to avoid cross-region moves (creating new Dependencies), and abandoning multi-region strategies (reducing redundancy and increasing Criticality). The pricing affects volume directly but warps everything else indirectly.

A 500TB cold archive with low dependency, low criticality, and low velocity is technically easy to move. The only barrier is the $40,000+ egress bill. That’s not gravity. That’s lock-in.

Regulatory Gravity

This is the policy-driven source: Regulatory gravity forces criticality by making data location a compliance requirement, regardless of whether location actually affects the other dimensions.

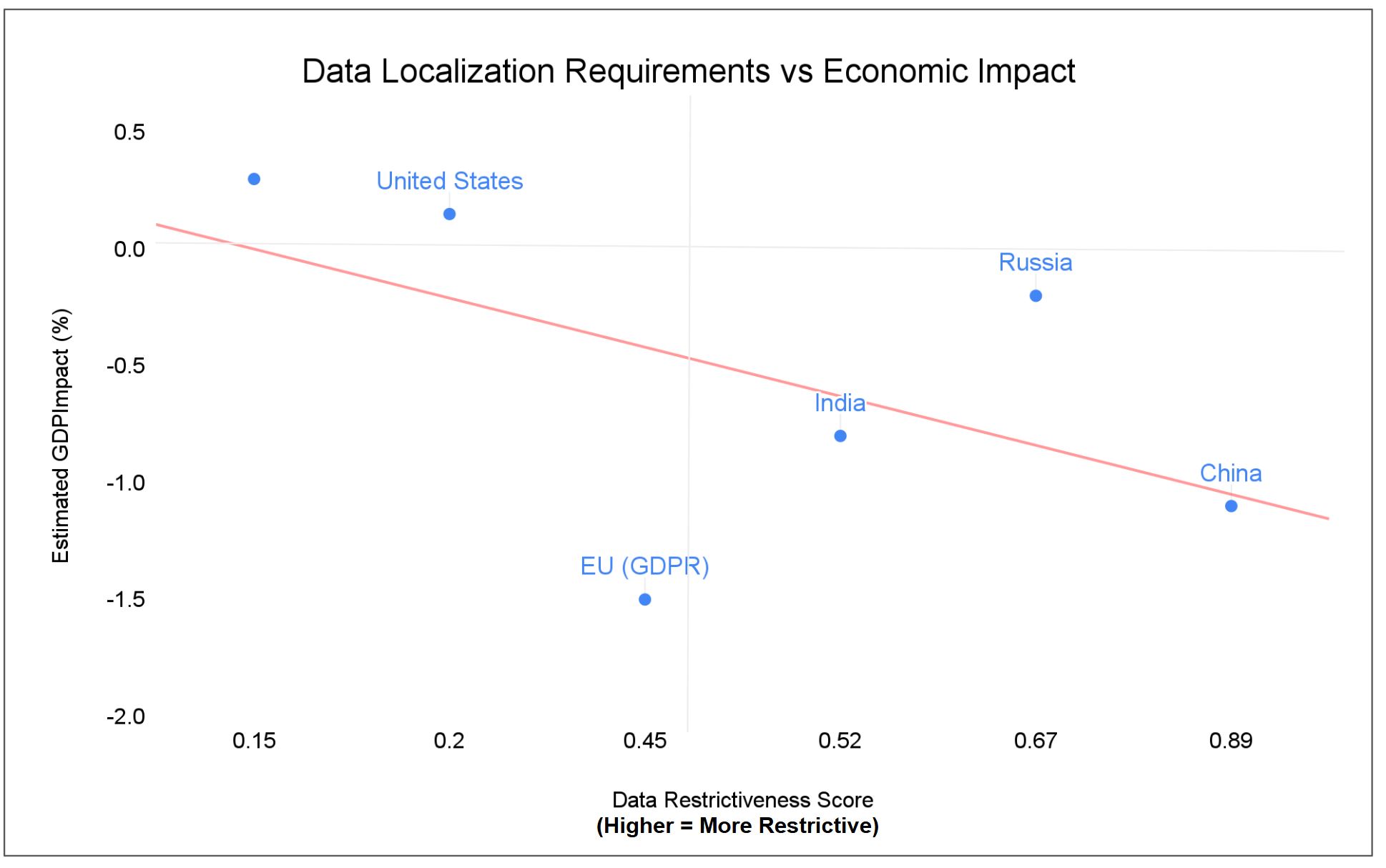

Countries impose data localization requirements citing national security and data sovereignty. The economic impact is measurable. The security benefit is not.

China’s strict data localization correlates with an estimated -1.1% GDP impact by 2025. Security improvement? Unmeasured, because breach data isn’t publicly reported. Russia’s 2015 data residency law: -0.2% GDP impact. Breach reduction? Also unknown. The EU’s GDPR-driven restrictions: estimated -1.5% GDP impact (roughly €200B by 2025 if strict localization were enforced at the member-state level).

Meanwhile, countries with open data flows show different patterns. The United States (minimal data restrictions) sees an estimated +0.1 to +0.2% GDP benefit from free data flows and runs the world’s largest digital services trade surplus. Singapore’s pro-free-flow policies contribute an estimated +0.3% GDP benefit, positioning it as a regional data hub.

Figure 3: OECD Data Restrictiveness Score vs GDP Impact

Here’s what’s revealing: countries with the strictest data localization (China, Russia) report the fewest data breaches publicly. Not because they’re more secure, but because they’re less transparent. The U.S. reports the highest number of breaches (1,802 in 2023) and highest per-capita breach costs (~$80 versus the EU’s ~$8), but experts attribute this to better reporting standards and higher business valuations, not worse security practices.

There’s no clear evidence that keeping data onshore reduces breach frequency or impact. Breach outcomes depend on cybersecurity maturity, incident response capabilities, and regulatory enforcement – not physical data location.

What data localization does reliably: it artificially increases criticality by making data location a regulatory requirement. Your 500TB data lake might have low business criticality, but if it contains EU citizen data and you’re not GDPR-compliant, it suddenly has extreme regulatory criticality.

Institutional Gravity

There’s a source of gravity that can’t show up in any volume-based metric but might be the strongest force of all: institutional knowledge. That Oracle database isn’t stuck because of technical constraints or economic penalties. It’s stuck because only three people in your organization know how to migrate it safely, and two are retiring next year.

The numbers tell the story. McKinsey research shows that 70% of large-scale transformation efforts fail, often due to loss of institutional knowledge rather than technical barriers. The average COBOL specialist is between 45 and 55 years old, with significant portions retiring each year. Over 71% of Fortune 500 companies still rely on legacy mainframes built by people who are now gone.

Pennsylvania spent $170 million over 7 years trying to modernize a COBOL unemployment system before declaring failure. The problem: loss of “tribal knowledge” as veteran staff retired. In 2020, New Jersey’s governor made an urgent public plea for COBOL programmers when unemployment claims surged and no one could modify the 40-year-old mainframe.

A 1TB database requiring specialized knowledge has more gravity than a 100TB standard system. Unlike technical constraints, institutional gravity compounds over time. Each retirement, each undocumented customization increases the weight. Organizations often don’t discover the problem until migration when they realize the system “worked fine” only because a few people carried all the knowledge in their heads.

Measurement Gravity

This is the measurement-driven source: When you measure data gravity primarily by volume, you create incentives that amplify volume-based gravity while hiding the other dimensions.

The DGx ranks metros by GDP, data center capacity, and aggregate storage. It doesn’t measure dependency, criticality, velocity, or latency requirements. Infrastructure planners don’t blindly follow DGx scores, but the index influences their analysis. Cloud providers price based on volume. Regulators count petabytes. The measurable dimension gets weighted heavily in decision-making, while the other four dimensions remain largely invisible.

This creates a feedback loop: measure volume → decisions optimize for volume → pricing reinforces volume → regulations track volume → measure volume again. A 10TB high-dependency, high-critical, high-velocity trading database gets treated the same as a 10TB low-dependency archive in pricing and regulatory frameworks because they have the same volume.

Figure 4: Feedback Impact on Data Gravity Workflow

The measurement problem drives real decisions:

- CIOs budget for storage costs, not switching costs

- Regulators set data transfer limits by volume, not by business impact

- Cloud pricing penalizes volume movement, not dependency untangling

- Infrastructure investments prioritize capacity over integration complexity

When you measure only one dimension, you become blind to the others. And what you can’t see, you can’t manage.

A Proposed Data Gravity Assessment Framework

We’ve established that data gravity has five dimensions (volume, dependency, criticality, velocity, latency) and five sources (technical, economic, regulatory, institutional, measurement). But understanding the components isn’t enough. To make this actionable, we need two more pieces: a way to score what we’re looking at, and decision logic for what to do about it.

Below is a condensed framework to demonstrate the concept. I’ve worked through the full scoring methodology, decision trees, and validation cases in a separate technical paper. Here, I want to show you how the framework works in practice.

Scoring Method

Score each dimension on a 1-5 scale:

| Dimension | 1 (Low) | 2 | 3 (Medium) | 4 | 5 (High) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Volume | <10GB | 10GB-1TB | 1TB-10TB | 10TB-1PB | >1PB | ||||

| Dependency | <5 systems | 5-20 systems | 20-50 systems | 50-100 systems | >100 systems | ||||

| Criticality | Convenience | Productivity | Revenue impact | Compliance | Life/safety |

| Velocity | Monthly | Weekly | Daily | Hourly | Real-time |

| Latency | Batch (hours) | <5 min | <1 min | <1 sec | <10ms |

Total score reveals gravity level: 5-12 is low, 13-20 is moderate, 21-25 is high.

For each high-scoring dimension, identify which sources created it. High volume from egress fees? That’s economic. High criticality from GDPR? That’s regulatory. High dependency because only three people understand the system? That’s institutional.

Testing the Framework

| System | Vol | Dep | Crit | Vel | Lat | Total | Assessment | Dominant Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital EHR (50TB, 20 apps) | 4 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 21 | High | Regulatory, Institutional, Ecosystem |

| Compliance Archive (1PB, 2x/year) | 5 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 12 | Low | Regulatory, Economic |

Hospital EHR System:

What the framework reveals: The system looks immovable, but two of the three dominant sources are changeable. Regulatory requirements are fixed, but institutional gravity can be reduced through documentation and training. Ecosystem lock-in can be addressed by building FHIR-based integration layers. The 50TB of data isn’t the problem – it’s the organizational and vendor dependencies.

Compliance Archive:

What the framework reveals: Despite having 20x more data than the EHR system, this archive has half the gravity. The petabyte volume creates a $40,000+ egress barrier, but that’s the only real obstacle. Low dependency and velocity mean migration can happen slowly over months without breaking anything. Economic gravity is negotiable – alternative providers charge nothing for egress. The volume makes it look stuck, but it’s actually one of the easiest systems to move.

Conclusion

I started with a simple question: when we experience data gravity, how much is organic constraint versus manufactured barrier?

The question evolved as I dug into the data. It’s not just “organic or manufactured” – it’s which dimensions are constrained by which sources, and which of those sources we can actually change. That refinement matters because it moves from “is this real?” to “what can we do about it?”

What I found: most of what we call data gravity is manufactured. Economic pricing creates artificial volume penalties 10-80x above actual costs. Regulatory requirements manufacture criticality without measurably improving security. Institutional knowledge gaps create dependency that has nothing to do with the data itself. And measurement systems that only track volume hide everything that actually matters.

The framework I’ve proposed here isn’t perfect. It’s deliberately simplified to expose patterns. Reality is messier – sources interact, dimensions correlate, edge cases abound. But even this simplified model reveals something useful: a 1PB compliance archive can have half the gravity of a 50TB hospital system. A 10TB trading database can be more stuck than systems 100x its size. Volume doesn’t equal gravity (or more simply – volume != value).

More importantly, manufactured gravity is often mutable. Economic sources can be negotiated in months. Institutional gravity can be reduced through documentation. Vendor lock-in can be abstracted with integration layers. The genuine technical constraints exist – physics is real, latency matters. But those constraints apply to a narrower set of workloads than most organizations assume.

This is one way to think about data gravity that might be more useful than counting petabytes. It won’t solve every problem, but it might help you figure out which problems are actually solvable.

The data isn’t as stuck as the bill suggests. Most of what keeps it in place isn’t physics – it’s pricing, policy, and the assumption that nothing can change.

Graph Citations

Graph 1: Cost to Move AI Training Datasets Out of AWS

- AWS pricing data: AWS EC2 Data Transfer Pricing

- Dataset sizes based on: OpenAI GPT-3 paper, ImageNet, LAION-5B dataset documentation

Graph 2: AWS Egress Pricing vs. Actual Bandwidth Costs

- AWS egress pricing: AWS EC2 Data Transfer Pricing

- Azure egress pricing: Azure Bandwidth Pricing

- Google Cloud egress pricing: Google Cloud Network Pricing

- Actual bandwidth costs based on: Cloudflare R2 pricing (zero egress), Akamai Connected Cloud pricing, and TeleGeography IP Transit Pricing (wholesale transit rates)

Graph 3: Data Localization Requirements vs Economic Impact

- Data restrictiveness scores: OECD Digital Services Trade Restrictiveness Index

- GDP impact estimates: ECIPE – The Costs of Data Localization